Good office lighting underpins almost every aspect of workplace design, yet it’s still one of the elements most often revisited late in a project.

This guide brings together the core principles that shape effective office lighting in the UK. It aligns with BS EN 12464-1, Part L, BS EN 1838 and TM66, and links to deeper technical resources across the Lumenloop knowledge base.

The aim is not to prescribe a single design approach, but to give a clear framework for evaluating options, avoiding common pitfalls and integrating lighting effectively within wider architectural, mechanical and user-experience considerations.

1. What Makes Good Office Lighting?

1.1 Key objectives

When designing for commercial workspaces, lighting must satisfy several parallel requirements:

Provide consistent, task-appropriate illumination

Maintain visual comfort with controlled luminance and low glare

Integrate cleanly with architectural and mechanical services

Support flexible working styles and potential layout changes

Reduce operational energy and meet relevant efficiency standards

Work alongside daylight, not against it

Daylight remains a critical component of perceived quality. The guidance within BS EN 17037 on daylight in buildings is increasingly referenced in office refurbishments and new-builds, particularly where planning requirements emphasise daylight access.

1.2 Impact on performance and comfort

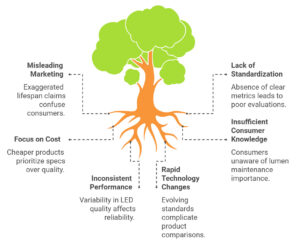

For specifiers, the discussion around “wellbeing” is often simplified, but the fundamentals matter: poor optical control, excessive contrast, colour inconsistency or minor flicker can all influence concentration and visual comfort across a full working day. Issues such as erratic uniformity or luminaires installed without regard for screen orientation remain common, even in modern CAT A schemes.

The cognitive influence of light is covered in the guide to the neuroscience of light, but for practical design purposes, the focus is on glare management, distribution, vertical illumination and colour stability — all of which contribute to a comfortable working environment.

1.3 Components of a functional office lighting scheme

A typical scheme will combine:

Ambient lighting (panels, linear systems or a mixture of both)

Task lighting where tasks demand higher precision

Accent or feature lighting to articulate architectural volumes

Controls designed around occupancy and daylight behaviour

The selection of luminaire types should follow the spatial requirements, ceiling constraints, maintenance strategy and preferred optical approach, rather than defaulting to standard panel grids.

2. Office Lighting Standards and UK Regulations

Office lighting sits at the intersection of visual comfort, building compliance and operational efficiency. For specifiers, the challenge is rarely “meeting the standard”; it’s meeting the standard while integrating with ceiling coordination, energy modelling, workplace strategy and budget realities.

The sections below summarise the regulatory foundations most relevant to UK office environments.

2.1 BS EN 12464-1: Key Requirements for Offices

BS EN 12464-1 defines minimum illuminance, glare limits, colour performance and uniformity — the baseline for task-appropriate visual conditions.

Specifiers working on CAT A or CAT B fit-outs typically focus on:

| Requirement | Typical Office Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Maintained illuminance (Em) | 500 lux | For general office tasks and computer work |

| UGR | <19 | Requires correct optics and spacing |

| Uniformity (U₀) | ≥0.6 | Avoids distracting contrast across the workplane |

| CRI | ≥80 | Some design studios may require CRI 90+ |

| Colour temperature | 3000–4000K | 4000K dominates open-plan spaces |

When reviewing existing buildings, it’s common to find that UGR, not lux levels, is the limiting factor.

Optical performance varies widely between panel types, which is why many designers rely on controlled optics rather than legacy opal diffusers.

A more detailed breakdown can be found in your technical guide to workplace lighting standards, which expands on the calculations and compliance checks.

2.2 Emergency Lighting in Office Environments

Emergency lighting must comply with BS EN 1838 and BS 5266. In practice, the specifier’s role is to ensure:

Escape route illumination is continuous and unobstructed

Minimum 1 lux on the centreline (often higher in real-world designs)

Signage is legible and correctly positioned

Luminaires offer suitable autonomy for the building strategy (30, 60 or 120 minutes)

In multi-tenant buildings, responsibilities are usually split: landlords address base-build compliance, while tenants handle layout changes, testing regimes and luminaire replacement.

Maintenance strategies are covered in your guide on emergency lighting responsibilities, which is useful when advising FM teams on testing intervals and record keeping.

2.3 Daylight Requirements and Integration

Daylight has a growing influence on both design quality and planning discussions. BS EN 17037 covers four core aspects:

Minimum daylight exposure

Directional view quality

Protection from direct sunlight

Glare considerations

Designers increasingly refer to the daylight guidance when assessing perimeter workstation layouts or evaluating whether a ceiling system needs supplemental lighting near façades.

In refurbishments, daylight analysis often shapes decisions around linear versus panel-based solutions, particularly in long floorplates.

Your article on BS EN 17037 daylight in buildings goes deeper into factors such as daylight autonomy and view quality, which can help justify spatial changes during early RIBA stages.

2.4 Part L and Energy Performance Requirements

Part L focuses on reducing operational energy and improving building efficiency. For lighting, this typically translates into:

Minimum luminaire efficacy targets

Effective zoning and control strategies

LENI calculations for new-build and major refurbishments

Integration with occupancy and daylight controls

Lower standby power and improved driver efficiency

While many office schemes still rely on basic presence detection, more advanced approaches — such as daylight-linked dimming or corridor-hold functions — produce significantly better LENI outcomes. The guidance on using lighting controls to meet Part L requirements discusses practical control strategies that align with energy modelling expectations.

Example: How design decisions affect LENI outcomes

| Design Choice | Impact on LENI | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-efficacy linear luminaires | ↓ LENI | Reduces baseline consumption |

| Daylight harvesting | ↓↓ LENI | Especially effective near façades |

| Poor luminaire spacing | ↑ LENI | Over-lighting increases energy use |

| Presence-only control | Variable | Depends on occupancy patterns |

| Scene-based control | ↓ LENI | Reduces unnecessary output in meeting rooms |

For BCO-compliant workplaces, the combination of high-efficacy luminaires and smart zoning usually provides the strongest performance without compromising design intent.

3. Designing an Office Lighting Layout

Designing an office lighting scheme is rarely a linear process. Architectural constraints, ceiling services, workstation layouts, glare control and energy targets all pull in different directions. A well-structured design approach helps avoid late modifications that are expensive to correct and disruptive during commissioning.

3.1 A Practical Workflow for Office Lighting Design

Most specifiers follow a process similar to the one below, regardless of whether the project is CAT A, CAT B or a targeted refurbishment.

Typical RIBA-Aligned Workflow

| Stage | Key Actions | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Brief + Strategy | Understand tasks, occupancy, IT layouts, screen use and meeting room typologies | Space planning data is critical at this stage |

| Concept | Identify distribution type: panel grid, linear, mixed, or feature-led | Consider integration with acoustic rafts and HVAC |

| Technical Design | Run calculations, assess UGR, model daylight contribution | Tools such as the office lighting calculator assist early-stage estimates |

| Coordination | Resolve conflicts with sprinklers, diffusers, cable trays and partitions | Important for suspended systems and open soffits |

| Specification | Lock optics, CCT, CRI, dimming, emergency strategy and maintenance plan | TM66 scores may be requested at this stage |

| Commissioning | Configure controls, verify lux levels and test emergency systems | Post-occupancy evaluation recommended |

Using a tool such as the office lighting calculator during early development helps establish whether the intended layout is viable before deeper modelling begins.

3.2 Selecting the Right Luminaire Types

The choice of luminaire has a significant influence on uniformity, glare, appearance and flexibility. The aim is to match the optical distribution to the space, not simply fill the ceiling evenly.

Common Approaches in UK Offices

| Luminaire Type | Typical Use | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recessed LED panels | Open-plan areas | Cost-effective, fast installation | Limited glare control unless using microprismatic optics |

| Suspended linear lighting | Design-led CAT B, collaboration zones | Better visual comfort, architectural clarity | Requires coordination with MEP |

| Downlights | Corridors, breakouts, washlighting | Good modelling and vertical illumination | Inefficient for large areas |

| Wall lights | Receptions, stair cores | Adds contrast and depth | Not a primary light source |

For schemes using recessed systems, the article on recessed office LED panels outlines how different diffusers and optic types influence visual comfort.

Optical Control Is Usually the Priority

Specifiers frequently choose luminaires based on:

Quality of glare control (especially in low-ceiling offices)

Beam distribution (narrow, wide, asymmetric)

Ability to maintain uniformity without over-lighting

Consistency of CCT and CRI across product families

Compatibility with DALI or wireless control platforms

A luminaire’s photometric profile will dictate spacing more than lumen output alone.

3.3 Achieving Balanced Illumination

Uniformity is one of the most misunderstood aspects of office lighting. It is not about making everything equally bright; it is about maintaining a comfortable contrast level across the workplane and the surrounding environment.

Factors Affecting Uniformity

Ceiling height

Luminaire distribution

Surface reflectance (floors, furniture, partitions)

Distance between parallel rows

Daylight penetration and orientation

Specifiers often assess uniformity using both numerical outputs (U₀ values from calculations) and practical checks:

Example: Uniformity Assessment Checklist

Are luminaires spaced to avoid scalloping on walls?

Does the layout avoid high-luminance spots above screens?

Is vertical illumination adequate for faces during video meetings?

Are partitions casting unintended shadows?

Breakout areas may tolerate lower uniformity, whereas open-plan desk zones typically require tighter control.

3.4 Glare, Screen Work and Visual Comfort

Glare management remains one of the most common concerns raised by clients — and one of the quickest ways a good scheme can be undermined.

Types of Glare to Consider

| Type | Description | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Discomfort glare | Light sources within the field of view cause eye strain | Influences perceived quality of the space |

| Disability glare | Reduces contrast and ability to see tasks clearly | Particularly relevant for screen-heavy environments |

| Reflected glare | Light bouncing off screens or glossy surfaces | Common with poorly spaced panels |

A deeper explanation of glare behaviour and UGR methodology is outlined in the guide to unified glare rating.

Positioning Relative to Screens

The most common coordination issue is luminaires installed directly above screen rows, creating high-angle reflections. Many specifiers now combine:

Narrower beam distributions in desk zones

Linear luminaires running perpendicular to desk rows

Higher vertical illumination for faces during calls

More controlled microprismatic diffusers rather than basic opal panels

Where office layouts shift frequently, a mixed approach (linear perimeter lighting + modular central clusters) improves adaptability.

4. Colour, Optics and Visual Quality

Colour quality and optical control directly influence visual comfort, accurate task performance and the perceived refinement of an office environment. These factors are often undervalued in early-stage design discussions but become critical during commissioning when users begin interacting with the space.

4.1 Colour Temperature in Offices

Choosing the correct colour temperature (CCT) is not simply an aesthetic decision. It shapes alertness, visual clarity and the overall character of the workspace.

Typical CCT Uses in Commercial Offices

| Area Type | Common CCT | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Open-plan workspaces | 4000K | Neutral white for clarity and screen work |

| Boardrooms | 3500–4000K | Balanced for video calls and mixed tasks |

| Focus rooms | 3000–3500K | Warmer tones reduce perceived intensity |

| Breakout / social zones | 3000K | Creates a softer, more relaxed environment |

| Design studios | 4000K (sometimes tunable) | Supports accurate colour judgement |

Specifiers increasingly use tunable systems in flexible CAT B schemes, although fixed-CCT solutions remain dominant due to simplicity and maintenance considerations.

4.2 Colour Rendering

High-quality colour rendering is essential in environments where materials, finishes or printed media matter. Even in general offices, stable CRI performance contributes to comfort and consistency across the floorplate.

Your guide to colour rendering and CRI explains how spectral quality influences the accuracy of colour perception and why certain applications may justify CRI 90+ sources.

Key CRI Considerations for Specifiers

CRI 80+ is sufficient for most office tasks

CRI 90+ is recommended for design studios or client-facing material review areas

R9 values should be checked when specifying higher-CRI luminaires

CRI consistency across a product family matters more than peak performance from a single fitting

Matching CCT and CRI across open-plan and meeting areas avoids visual mismatches during transitions.

4.3 Optical Control and Distribution

Optics determine how light moves through a space — influencing uniformity, glare, vertical illuminance and perceived brightness. Unlike lumen output, optics cannot be “corrected” later in the design; they must be chosen correctly upfront.

Common Office Optics and Their Uses

| Optic Type | Suitable Uses | Advantages | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microprismatic diffusers | Open-plan areas | Good high-angle control; UGR compliance | More comfortable than opal diffusers in low ceilings |

| Opal diffusers | Breakout areas, corridors | Soft appearance; cost-effective | Higher risk of UGR issues above screen rows |

| Baffles / louvres | Linear suspended luminaires | Strong glare control | Useful in open soffits and exposed ceilings |

| Asymmetric optics | Wallwashing, circulation | Enhances vertical illumination | Supports visual hierarchy and navigation |

| Narrow beam optics | Focused or feature areas | Accent and contrast modelling | Not suitable for general ambient illumination |

For specifiers working on workspace refurbishments, optical control often determines whether BS EN 12464-1 values are achievable without excessive over-lighting.

4.4 Vertical Illumination and Modern Workstyles

Video calls, face-to-face collaboration and mixed digital tasks have increased the importance of vertical rather than purely horizontal illumination. Overhead uniformity alone doesn’t guarantee good facial modelling or comfortable visual conditions for hybrid working.

Practical considerations

Linear luminaires running perpendicular to desks provide better face lighting

Wallwashing increases perceived brightness without raising lux levels

Controlled optics reduce harsh shadowing on faces during video calls

Balanced vertical illumination improves wayfinding and spatial perception

Designers often use a combination of suspended linear lighting and controlled recessed systems to achieve a visually balanced environment.

5. Lighting for Wellbeing and Human Performance

Workplace wellbeing is often discussed in broad terms, but for specifiers the focus is far more practical: reducing visual fatigue, improving long-term comfort and supporting consistent performance throughout the working day. Lighting is only one element of this, but when poorly executed it becomes a major source of complaints.

5.1 Reducing Eye Strain in Office Environments

Visual fatigue typically arises from a combination of glare, contrast imbalance, poor distribution and inconsistent colour temperature. These issues are not always visible in early renders but become obvious once users are seated at workstations.

Your guide to reducing eye strain with office lighting discusses these interactions in more detail, especially around uniformity and screen reflections.

Key design considerations

Ensure luminaires are not positioned directly above monitor rows

Use microprismatic or baffled optics to reduce high-angle luminance

Maintain consistent CCT within each zone

Minimise dark surfaces that create high contrast ratios

Avoid excessive brightness drops between open-plan and corridor areas

Where offices rely heavily on laptops, the plan should consider the wider range of viewing angles and mobile workstation locations.

5.2 Managing Blue Light in Offices

Blue light is a frequent topic of discussion in workplace health assessments. In practice, most concerns relate to:

Excessive luminance rather than spectrum

High contrast between screens and surroundings

Poorly balanced ambient light

Overly cool CCT used in relaxation or breakout spaces

The article on blue light in workplace environments provides a realistic view of what actually influences comfort and circadian stability, separating it from common misconceptions.

Practical observations

4000K does not create harmful blue light exposure

Large contrasts between screen brightness and ambient light are more fatiguing than blue-rich spectra

Tunable systems can ease transitions between task work and collaborative zones

Blue light discussions are often overstated, but they can highlight broader design issues around distribution and task-environment balance.

5.3 Circadian and Time-of-Day Lighting

While full circadian systems are still uncommon in general offices, certain design elements can support a more natural working rhythm.

Relevant principles are covered in your guide to circadian approaches to office lighting, particularly around melanopic ratios and daylight coordination.

Where circadian-aligned strategies are most effective

Teams working extended hours or shift-based patterns

Areas without access to natural light

Environments where alertness and consistency are critical

Hybrid workspaces with variable occupancy profiles

Specifiers should consider whether tunable lighting genuinely adds value or whether a consistent, neutral white solution (around 3500–4000K) is sufficient.

5.4 Lighting for Neurodivergent-Friendly Workplaces

Lighting can significantly influence comfort for neurodivergent occupants, particularly those sensitive to flicker, glare and rapid light level changes.

Design strategies

Use flicker-free drivers and consistent dimming curves

Avoid exposed LED points in open-soffit designs

Maintain predictable illumination across circulation routes

Provide localised control where possible

Limit dramatic colour shifts or saturation in key work areas

These adaptations often align naturally with good lighting practice, resulting in a workspace that is more comfortable for all users.

6. Energy Efficiency and Smart Lighting Controls

Energy performance is now central to office lighting design, especially in the context of Part L, rising operational costs and ESG reporting. Lighting controls are no longer optional extras; they are fundamental to achieving compliant and efficient buildings.

6.1 Improving Lighting Efficiency Without Compromise

While luminaire efficacy is important, overall performance depends on design decisions made much earlier in the process.

The guide on improving office lighting efficiency outlines practical ways to reduce operational demand without affecting comfort or compliance.

Primary factors influencing consumption

Choice of luminaire optics and distribution

Avoidance of unnecessary over-lighting

Daylight integration

Control zoning and occupancy patterns

Driver efficiency and standby load

Luminaire spacing and optical control often have greater impact on energy performance than raw lumen-per-watt figures.

6.2 Control Strategies for Modern Offices

Controls determine how lighting behaves throughout the day, and the differences between basic and optimised approaches can significantly affect LENI outcomes.

Your guide on efficient lighting control options provides an overview of strategies that are now standard in high-performing workplaces.

Common control methods

| Control Type | Typical Application | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Presence detection | Cellular offices, washrooms, small meeting rooms | Simple and cost-effective |

| Absence detection | Open plan areas | Reduces false-on behaviour |

| Daylight dimming | Perimeter zones | Strongest impact on LENI |

| Time scheduling | Multi-tenant floors | Reduces after-hours load |

| Scene control | Boardrooms, collaboration areas | Supports hybrid meeting requirements |

Specifiers should ensure control strategies are clearly documented in tender packages to avoid value-engineering that removes key functions.

6.3 DALI, Wireless Control and System Selection

Control protocol decisions influence maintainability, commissioning and integration with wider building systems.

A comparison is explored in your guide to DALI vs Casambi, along with the article on Casambi wireless smart lighting.

Considerations for each approach

DALI: Robust, predictable and widely understood by contractors; well suited to larger CAT A schemes.

Wireless (e.g., Casambi): Flexible, rapid to deploy and ideal for CAT B projects or refurbished spaces where wiring routes are limited.

Hybrid systems: Increasingly common where base-build DALI is combined with wireless extensions for tenant fit-out layers.

Wireless solutions also simplify reconfiguration as corporate space plans evolve.

6.4 Estimating Energy and Cost Savings

Early-stage modelling can identify whether proposed layouts or luminaire choices will meet project targets.

The office lighting calculator is typically used at feasibility stage to check that the concept is not over-lighting the space or producing excessive wattage per square metre.

Example: Influence of Key Design Variables on Energy Use

| Variable | Effect on Energy Consumption | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Luminaire efficacy | Moderate impact | Gains often offset by poor optical control |

| Spacing and distribution | High impact | Over-lighting inflates LENI |

| Daylight integration | Very high impact | Façade zones offer most opportunity |

| Control zoning | High impact | Independent room control prevents unnecessary run-time |

| Standby load | Moderate | Important in large multi-floor buildings |

When working on ESG-driven projects, small improvements across several variables often yield better results than a single high-efficacy luminaire choice.

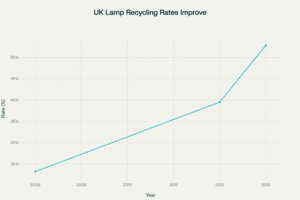

7. Sustainability and Circularity in Office Lighting

Sustainability requirements now appear in most commercial briefs, driven by corporate ESG targets, landlord obligations and long-term maintenance considerations. Lighting contributes to both operational and embodied carbon, which is why more clients expect circularity metrics, TM65/TM66 data and refurbishment pathways to be documented at specification stage.

7.1 Why Circular Design Matters in Workplaces

A typical office lighting system lasts several years, but the quality of design and product selection determines how easily it can be repaired, upgraded or repurposed rather than discarded. This links closely with emerging expectations in commercial leasing, where landlords aim to avoid unnecessary waste at each tenant changeover.

Your overview of circular economy lighting principles outlines how material choices, modularity and serviceability influence lifecycle performance.

Key considerations for circularity

Replaceable LED modules and drivers

Standardised components for ease of maintenance

Durable housings that support multiple refurbishment cycles

Minimised adhesives and welded joints

Accessible emergency gear for end-of-life testing and replacement

Circularity is no longer limited to specialist projects; it is increasingly a requirement in major commercial tenders.

7.2 TM65 and TM66 for Embodied Carbon and Circularity

TM65 provides a method for estimating the embodied carbon associated with luminaires, while TM66 focuses on circularity and product lifecycle performance. These methodologies allow specifiers to compare luminaires beyond efficacy or upfront cost.

Your guide to the new circular economy standard explains how manufacturers are responding with more transparent material reporting and modular product design.

Typical project uses for TM65/TM66

Supporting planning submissions

Demonstrating compliance with client ESG frameworks

Comparing refurbishment versus replacement options

Providing quantifiable sustainability metrics at tender stage

7.3 Material and Component Strategies

Lighting contributes to waste not only through failed components but also through luminaires that are not designed to be repaired.

Preferred characteristics

Aluminium housings that resist deformation

Tool-free access to drivers and emergency gear

Replaceable optical films and diffusers

Long driver lifetimes with clear documentation

Compatibility with third-party emergency systems

These factors reduce waste and lower long-term costs for building operators.

7.4 UK Manufacturing and Supply Chain Advantages

UK-made luminaires support circular design because:

Components can be refurbished or replaced locally

Lead times are shorter and more predictable

Manufacturer support is easier to access for multi-tenant buildings

Transport emissions are reduced compared with overseas sourcing

For FM teams, a local refurbishment model often results in faster issue resolution and lower replacement rates.

8. Lighting Approaches for Different Office Spaces

Different workspace typologies demand different lighting strategies. A single distribution type rarely works well across an entire floorplate; instead, designers use a combination of optics and mounting styles to support diverse user needs.

8.1 Open-Plan Offices

Large floorplates require controlled optics, consistent spacing and strong uniformity.

Designers typically prioritise:

UGR < 19

Neutral white CCT (usually 4000K)

High vertical illumination to aid visual communication

Good integration with ceiling systems, especially in exposed soffit schemes

Linear lighting running perpendicular to desk rows remains one of the most effective open-plan solutions.

8.2 Small Offices and Cellular Rooms

Cellular spaces benefit from slightly softer distribution and more predictable lighting patterns.

Design considerations

Avoid harsh downlight beams above screens

Provide localised dimming or scene control

Maintain consistent CCT with adjacent open-plan areas

Incorporate wallwashing or indirect elements where possible

Smaller rooms also offer opportunities for modest energy savings through absence detection and tailored schedules.

8.3 Boardrooms and Meeting Spaces

Hybrid working has increased the importance of vertical illumination and camera-friendly lighting conditions.

Key requirements

Balanced frontal illumination for faces during video calls

Avoidance of strong downlight shadows

Scene presets for presentations, calls and collaboration

Controlled reflection behaviour on screens and whiteboards

Linear or edge-lit systems generally produce better results than traditional downlights.

8.4 Breakout and Collaboration Zones

Breakout areas benefit from warmer tones and more relaxed lighting patterns. These spaces support varied tasks, so lighting should adapt accordingly.

Practical strategies

3000–3500K CCT for a softer feel

Combination of indirect and diffuse light sources

Accent lighting to create visual contrast

Independent control to differentiate from open-plan zones

8.5 Receptions, Circulation and Touchdown Spaces

These areas often set the tone for visitor experience while supporting navigation and safety.

Typical requirements

Higher vertical illumination for wayfinding

Accent lighting to define architectural features

Clearly lit reception desks and access control points

Robust emergency lighting integration

These spaces also present opportunities for improved energy performance through occupancy-based control.

9. Retrofitting and Upgrading Office Lighting

Retrofitting has become a major part of commercial lighting work, particularly in buildings undergoing repeated CAT B churn.

A clear retrofit strategy ensures compliance, efficiency and visual consistency without major disruption.

9.1 Identifying When an Upgrade Is Necessary

Common indicators include:

Noticeable colour shift across fittings

Poor uniformity or excessive shadows

Legacy emergency systems with ageing batteries

High maintenance costs due to driver failures

Over-lighting from outdated specifications

Upgrades are also driven by Part L requirements in major refurbishments.

9.2 Retrofit Pathways in Commercial Offices

The article on LED office retrofit upgrades outlines different approaches, from simple panel replacements to full optical redesigns.

Common retrofit options

| Retrofit Type | Best Use Cases | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Panel-for-panel replacement | Existing grid ceilings | Ensure optic choice meets UGR requirements |

| Linear system upgrade | CAT B design refresh | Can significantly improve visual comfort |

| Emergency bulkhead replacement | Aged systems / non-compliant layouts | Supports modern testing regimes |

| Mixed retrofit + recontrol | Hybrid spaces | Adds flexibility without structural changes |

Where possible, retain existing housings or ceiling infrastructure to minimise waste.

9.3 Minimising Disruption During Upgrades

Office tenants often remain operational during retrofit works, which makes planning essential.

Strategies to reduce impact

Use modular systems that install rapidly

Coordinate with FM teams to phase works out of hours

Provide temporary emergency lighting during replacement

Commission controls in stages to avoid downtime

Ensure clear documentation for future reconfiguration

Minimising disruption is particularly important in multi-floor corporate buildings where retrofit timelines are tight.

10. Office Lighting FAQs

These questions frequently arise during early-stage discussions with clients, facilities teams and project managers.

What lux level is recommended for offices?

Most desk-based tasks require around 500 lux. Meeting rooms typically range from 300–500 lux depending on task type and AV requirements.

What colour temperature works best?

4000K is typically used for open-plan and technical zones. Warmer tones (3000–3500K) suit breakout and reception areas.

How can glare be reduced?

Use controlled optics, microprismatic diffusers, perpendicular linear lighting and careful spacing relative to screens. Glare performance should always be checked against UGR values in BS EN 12464-1.

How much energy can smart controls save?

Daylight dimming and presence-based control usually deliver the highest reductions in LENI. Savings vary, but a well-controlled perimeter zone can reduce consumption by more than 20–40% depending on façade orientation.

What are the emergency lighting requirements for offices?

Escape routes, open areas and critical points must meet BS EN 1838 and BS 5266. Testing and logbook responsibilities depend on the building’s management structure.

Conclusion

Well-designed office lighting is the result of careful integration between architectural intent, regulatory compliance, optical performance and long-term maintainability. For specifiers and consultants, the challenge is not simply to meet standards, but to deliver lighting that supports comfort, collaboration and efficient operation throughout the building’s lifecycle.

This guide links to deeper technical resources across the Lumenloop knowledge base, allowing you to explore each element in more detail and apply these principles effectively in your own projects.